SAVING

THE GREAT LAKES*

One of the many issues

facing Michigan’s Governor comes to her from a Canadian business. This firm is Enbridge,

a Canadian multinational pipeline and energy company headquartered in Calgary,

Alberta, Canada. Enbridge owns and operates pipelines throughout Canada and the

United States, transporting crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids

from the far west of Canada to and through the United States. Founded in 1949, more

recently the company has also entered the newly-found business of generating

renewable energy as they seek to improve their profit margins and increase

their presence in creating energy as well as just moving it.

Enbridge's pipeline

system is the longest in North America and the largest oil export pipeline

network in the world (See map on a following page), thus affording them

considerable influence in both Canadian and U.S. politics. Recently, President

Biden and Prime Minister Trudeau were involved in talks but Biden declined to

discuss Enbridge’s unwelcome legal challenges to Michigan’s Governor Gretchen

Witmer.

Enbridge

pipelines for crude oil are 17,809 miles long while Its 23,800 miles of natural

gas pipelines connects multiple Canadian provinces, several US states, and the

Gulf of Mexico. Enbridge has evolved a naming and or numbering system for each

of its major pipelines. Their ‘line five’ pipeline is the object of this

paper as it runs from Superior Wisconsin across Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and

then under water at the Straits of Mackinaw, thence overland to its refinery in

Sarnia, Canada.

The

bane of petroleum pipelines are leaks (often called spills by the industry). The

poisonous gases and oils pumped through pipelines quickly spread from ruptured

pipelines to the surrounding substrata causing contamination of soils and water

from the toxic oils and gases.

*Much of this article was prepared by Traverse City writer BARBARA

STAMIRIS on MAY 6, 2023

The effluent

can be responsible for killing wildlife, fouling beaches, and poisoning water

tables that are often the source of drinking water.

Enbridge has been responsible for

several oil spills, including spills on their lines 3,

5 and 6. A leak occurred on their line 3 on March 3 1991 when operators failed

to shut down the pipeline for three hours after the pressure drop was first

noticed. This spill was the largest ever in the history of the U.S. The Line 3 pipeline was also the origin of a 1.3 million-gallon

oil spill in 1973, the second worst in Minnesota history.

Major pipelines in North America

Another

Enbridge spill known as the ‘Kalamazoo River oil spill’ occurred in July

2010 when Enbridge’s Line 6B burst and flowed

into a tributary of the Kalamazoo River near Marshall, Michigan. This pipeline carried heavy crude oil

known as diluted bitumen.

Following the spill, the volatile diluents evaporated, leaving the heavier

bitumen to sink in the water. Thirty-five miles of the Kalamazoo River were

closed for clean-up until June 2012, when portions of the river were re-opened.

On March 14, 2013, the EPA ordered Enbridge to return to dredge portions of the

river to remove submerged oil and oil-contaminated sediment.

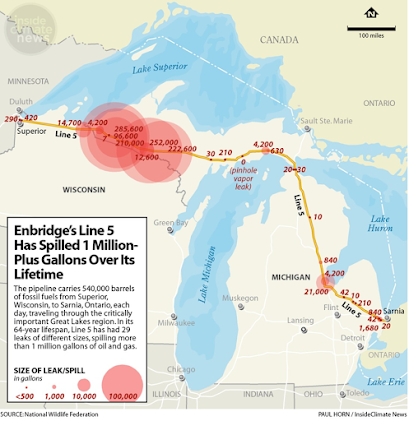

Line 5 is an Enbridge pipeline that originates in Superior

Wisconsin (just south of Duluth). The line traverses Michigan’s Upper Peninsula

reaching the Straits of Mackinaw on its southeastern course. At the Straits,

the builders of the line sent the line underwater at the Straits. The line then

resumed its cross-country direction back toward Canada until it terminated in

Sarnia where Enbridge has a refinery operation. Line 5 has leaked 33

times in Michigan lands and waterways as it carries oil to Sarnia. See the following

map.

The upper reaches of

Line 5 cross the Bad River tribal land. The Indians complained to the firm that

the risk of leaks on their land had increased over the years, and besides, they

said, the agreement to cross reservation lands ended in 2013: Enbridge

continued to flow petroleum through the pipeline anyway The Indians sued and

the judge ruled in favor of the Indians.

MADISON, Wis. -- A federal judge has given Enbridge

three years to shut down parts of an oil pipeline that crosses reservation land

and ordered the energy company to pay a Native American tribe more than $5

million for trespassing.

When

Michigan Gov. Whitmer ordered Line 5 shut down in 2020 to protect the Great

Lakes, she gave the company and the State of

Michigan six months — until May 12, 2021— to develop a prudent decommissioning

plan. Enbridge has announced it will defy her shutdown order, instead suing to

keep Line 5. operating until a tunnel is completed that Enbridge says will help

prevent leaks. — a project estimated to take 5–10 years. Enbridge sued to

keep it operating, claiming that a 1977 treaty with the United States allowed

them to continue pumping oil through the critical waterways. That lawsuit is

still being litigated. While Enbridge lawsuits drag on, Line 5—well beyond its

50-year design life—continues to bring in billions by operating in defiance of

the state order.

Now 70 years old, Line 5 is the world’s most dangerous pipeline

due to its degraded condition and its position among our unique Great Lakes.

Michigan Senator Gary Peters supported the Governor’s action and

conducted a hearing on the topic. Experts who testified at the hearing called

the Mackinac Straits “the worst location in the U.S. for an oil pipeline.” Its

condition in this sensitive location makes Line 5 the most dangerous pipeline

in the U.S. and in the world. No other pipeline endangers 20 percent of Earth’s

freshwater, 700 miles of shoreline, and the drinking water of 40 million. Yet

Enbridge chooses the 70-year-old Great Lakes route instead of its seven-year-old land-based route to Sarnia.

Why is Line 5 so dangerous? In a busy shipping lane, anchor strikes are

inevitable. The many freighters that traverse the Straits are the cause of

anchor strikes that can and do, pull the pipeline from its moorings. Warnings

are ineffective, since dropping an anchor is an emergency measure. In 2018, an

anchor struck Line 5 pulling the pipeline off its moorings for several feet.

But anchor strikes are not the only risk to the pipeline. The Straits’ water currents,

10 times stronger than Niagara Falls, scoured away Line 5’s bottomland support

on several locations. As a result, Line 5 requires 219 remedial supports which

suspend it, causing new problems. Line 5 now sways in the currents, causing

bending and vibrational stress. A suspended pipeline represents a completely

new design, requiring engineering review and approval that it never got. Keep

in mind that the pipeline was never designed to move and bend when it was

originally designed over 70 years ago.

When the pipeline rubbed against the supports, its safety

coatings were scraped off—damage Enbridge failed to report for three years. In

2020, extensive damage to one of the supports led to months of shutdown.

Enbridge said its own vessel caused the isolated incident, yet forceful

currents from record-high lake levels could have caused the displacement and

affected other supports.

An Enbridge pipeline around the lakes, rebuilt and expanded after the Kalamazoo

spill, reopened in 2015 with excess capacity, but Enbridge chooses to continue

using the line through the Straits where it is positioned directly under the

Big Mac Bridge.

Another strategy that keeps Line open is Enbridge’s insistence

that building a tunnel under the water will make Line 5 safer to operate. Knowing

that Line 5 is obsolete, Enbridge said a tunnel would replace it by 2024. In

late 2023, the US Army Corps has announced a delay in its review of a tunnel

proposal which pushed tunnel completion to 2030. If a tunnel is built, Line 5

would be nearing 80 years old. If the tunnel is not approved, Enbridge has said

it will continue to operate old Line 5..

Enbridge publicly promotes a tunnel as the solution for Line 5, but its

internal plans differ. In the 2018 tunnel agreement with outgoing Gov. Snyder,

Enbridge made sure it could back out without penalty—a wise move since an oil

tunnel is not a safe investment today. This may explain why Enbridge’s Board of

Directors has not approved the tunnel and no money is allocated for a tunnel in

its annual Security & Exchange Commission Reports meant to inform

shareholders of upcoming projects. Enbridge has no plan or date for decommissioning

Line 5. They appear to believe that they can operated the old line forever

While Enbridge avoids risk, taxpayers must fund years of state

and federal review for a tunnel that is unlikely to be built.

In Ottawa this past March, Biden told Trudeau we’re “two countries with one

heart.” If the Great Lakes are that heart, warnings of a deteriorated and anchor-struck

pipeline, like warnings of a heart attack, cannot be ignored. And yet mention

of Line 5 was politely avoided.

Biden remained silent about Trudeau siding with Enbridge and

opening court case based on a 1977 treaty. The treaty asserts that Line 5 can’t

be shut down by Michigan, that the U.S. must transport Canada’s oil against our

own environmental and economic interests.

National Geographic says

the Great Lakes are “the irreplaceable fragile ecosystem…that our planet needs

to survive.” An oil spill here would have global implications; yet, unlike

other climate threats, this one can be solved by turning off a valve. While the

fix itself is easy, the politics are not. One thing is certain, Enbridge should

not get to decide on a risk that endangers the citizens of Michigan and the fisheries

in the Great Lakes.

From a planetary perspective, it’s a no-brainer. If the world’s most dangerous

pipeline has an easy solution, get the oil out of the water. Now.

Barbara Stamiris is an environmental activist

living in Traverse City